The middle school math that helps you park your car

Do you have a car? If so, you have probably more than once thanked your car's parking assist — you know, that rhythmic beeping that can guide you into an impossible parking space. What you may not know is that you are then also thanking a mathematical formula that is as well-known as it is hidden. A formula that can perform the feat of transforming distance into time.

Parallel parking mathematics

Our modern cars have ultrasonic sensors at the front and rear. These send out sound waves in all possible directions, at frequencies that cannot be heard by the human ear.

d is the distance from the car to surrounding objects

The sound waves bounce off objects around the car and then travel back to the sensor. By measuring how long it takes for the sound waves to return, the parking assist can calculate the distance to surrounding objects and start beeping rhythmically when you get too close. The trick? A little middle school math.

Let me show you the details.

Remember the formula d = s ∙ t? It says that if something travels at a constant speed, the distance traveled can be calculated by multiplying the speed by the time.

d = s ∙ t d is the distance, s is the speed och t is time

The sound waves emitted by the car's sensors travel at a constant speed of 340 meters per second. If we multiply 340 m/s by the time in seconds, we can calculate the total distance traveled by the sound waves since they were emitted.

d = 340 ∙ t

But the sound waves have traveled both from the car to the object and back, i.e. twice the distance we are interested in. Therefore, we must divide the result by 2.

If the sound waves bounce back to the sensor in two thousandths of a second, then it's easy to calculate that the object you want to avoid is 0.34 meters away.

d = 340 m/s · 0,002 s 2 = 0.34 m

And the parking assist started beeping a long time ago.

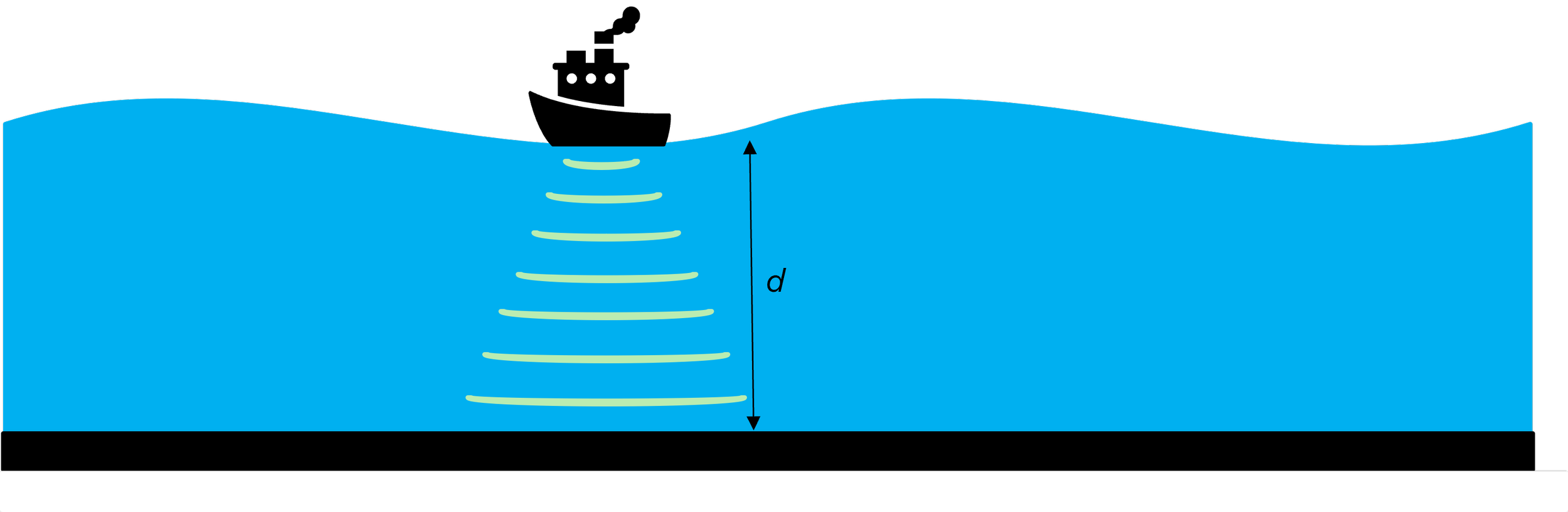

Sea depth with sound waves

But your car isn't the only machine that benefits from the relationship between distance, speed, and time. The same idea is used to measure ocean depths. By sending out sound waves and measuring how long it takes for the sound waves to return, a sonar can determine the distance to the bottom.

The only thing the sonar manufacturer needs to consider is that sound travels faster in water—at a speed of approximately 1,500 meters per second—so the formula will look like this:

d = 1 500 · t 2

Medical ultrasound

Perhaps more surprising is that the same idea—the same formula— is fundamental to the medical ultrasound.

Let's say you want to perform an ultrasound examination of a fetus. Using a transducer, you send ultrasound waves into the mother's abdomen. These sound waves will travel into the body. But when they encounter new tissue, a new structure, some of them will be reflected and bounce back to the transducer.

The amount of sound waves that bounce back provides information about the type of surface. Bones, for example, reflect a large proportion of the sound waves, while muscles or organs reflect a much smaller proportion.

Bones reflect a large proportion of the sounds waves

Organs reflect a smaller proportion of the sounds waves

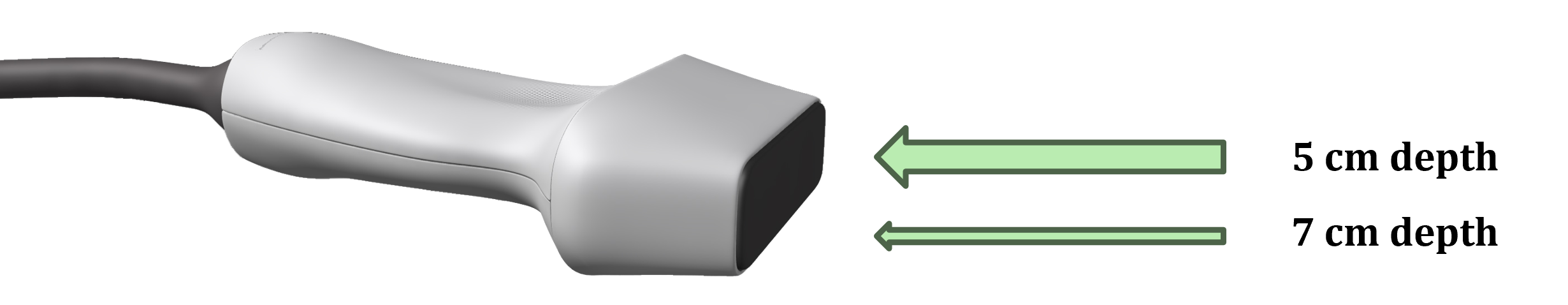

This information is captured by the ultrasonic sensor, which measures both the strength of the echoes and how long it took for them to return. Using the time, the sensor can - with the same formula as before - calculate a distance, in this case from which depth the echoes were reflected.

For example, the sensor could conclude that the stronger sound wave was reflected in a tissue only 5 cm deep, while the weaker sound wave took longer to return and was therefore reflected at a greater distance, perhaps 7 cm deep.

With the help of time, the transducer can determine the depth from which each sound wave was reflected.

This information is then used to create an ultrasound image, i.e., an image that shows what is present at different depths in front of the ultrasound transducer. Shallow structures—i.e., those that are close to the transducer—are displayed at the top of the screen, while deeper structures are displayed further down.

Ultrasound image created with AI.

What determines whether it’s black, gray, or white at a certain distance from the sensor is how strong the echo was from that particular tissue. Strong echoes, e.g. from a hard surface such as bone, are shown as white structures on the screen, while blood, which basically does not reflect any sound waves at all, is marked as black. And then there is a gray scale in between – a gray scale that can show everything from a serious medical condition to a new, pulsating life.

One key – many doors

How is it possible that a single formula can help us with such diverse things as parallel parking, determining ocean depths, and showing the inside of our bodies? The answer is that mathematics has the ability to capture the fundamental structure of a phenomenon. Once that structure becomes visible, it can often be recognized in other situations. For example, the formula that can convert time into distance also makes guest appearances in builders' laser measuring devices and in GPS's ability to locate your position. For me, that is one of the superpowers of mathematics—that it allows us to open completely different doors with one and the same key.